Raised Floors Are an Opportunity for Post Frame Homes

Three months after Hurricane Harvey churned through Texas, dumping 51 inches of rain and damaging an estimated 150,000 homes, the state’s most populous county took a bureaucratic step which has huge implications for how it will deal with the risk of future flooding.

On December 5, Harris County, which surrounds the City of Houston, approved an overhaul of its flood rules expanding them from 100-year floodplains—which have a one percent change of flooding in a given year—to 500-year floodplains. The new rules (which don’t apply inside Houston city limits) will compel people building houses in some areas to elevate them up to eight feet higher than before.

“We had 30,000 houses that flooded” from Harvey, said county engineer John Blount, who put forward the rule changes. Before the floodwaters even subsided, hundreds of county employees fanned out to survey the damage. “We went to every one of those houses and figured out how much water got in them, and then we did a statistical analysis,” Blount said.

The data was geocoded, factoring in location and neighborhood conditions, and one result was the increased elevation rule. (The county is also buying out 200 of the most vulnerable homes and hopes to buy out thousands more, but those represent a small fraction of the homes inside the floodplain.)

Harris County’s new rules are the most stringent flood-related development restrictions anywhere in the United States, according to Blount. If a future Harvey-sized deluge comes, almost all the homes in the area will be safe, he said: “Had that same event happened, at the same location but [with houses] built to the new standard, 95 percent or more would not have flooded.”

For a structure, standing water is a fearsome enemy. Even a small amount of flooding in a home can exile its inhabitants for weeks and require costly repairs. After Harvey, tens of thousands of evacuees lived in hotels or with friends as workers in their homes tore out drywall to prevent the spread of mold, which can sicken residents. And more Harveys are coming: As Robinson Meyer reported, a new MIT study concludes Harvey-scale flooding in Texas is six times as likely now as it was in the late 20th century, and will only get more likely as this century wears on.

More than a million people live in the 100- and 500-year flood zones across the Houston area, and hundreds of thousands more do in other U.S. cities, including Miami and New York. Harris County’s move conforms with the advice of building engineers, climate experts, and the insurance industry. If you live in an area which is prone to flooding—or will be soon—getting off the ground is the best way to avoid recurring, expensive, and heart-rending damage to your house.

“There’s no real substitute for elevation. That’s your best bet,” said Tim Reinhold, senior vice president and chief engineer of the Insurance Institute for Business and Home Safety (IBHS), a research organization based in Tampa and funded by insurers.

Houses don’t have an engineered safety margin for avoiding flooding the way they do for wind resistance, Reinhold points out; even a few inches of water can be devastating. His advice: “Build that margin in by going higher.” The IBHS recommends elevating houses three or more feet above the 100-year floodplain.

Yet three feet is nowhere near standard. The City of Houston requires one foot of elevation above the 100-year floodplain. Many jurisdictions in Texas and other states require none. What seems like a simple, obvious safeguard raises tricky questions: How high is high enough? Who has to pay for it? And at what point does it no longer make sense to build in a place at all?

Yet three feet is nowhere near standard. The City of Houston requires one foot of elevation above the 100-year floodplain. Many jurisdictions in Texas and other states require none. What seems like a simple, obvious safeguard raises tricky questions: How high is high enough? Who has to pay for it? And at what point does it no longer make sense to build in a place at all?

Nationwide, according to Census data, 59 percent of new single-family homes are “slab-on-grade,” as it’s known in the construction industry. The technique is pretty much what it sounds like: Concrete is poured into a mold set shallowly into the ground, forming a slab several inches thick. Because a ground freeze can crack the slab, the method is mainly used in warmer climates. It’s straightforward and cheap. But it results in a house with a low elevation, which is obviously not ideal in a flood zone. “I don’t understand why you would ever build a house on a slab on grade that could be in a flood-prone area,” Barcik said.

Building a house with a raised foundation isn’t cheap. “If you’re starting with a home that’s slab-on-grade right now, and want to raise it by using fill, it could be $13,000 to $14,000 to do that just one foot,” said Gary Ehrlich, the director of construction codes and standards for the National Association of Home Builders.

Mike the Pole Barn Guru comments:

The fill method—trucking in soil and resting the slab on top of it—is cheaper than the pier-and-beam or stem-wall options. But it’s not adequate for raising a house’s height by several feet. The eight-foot-elevated homes now required in parts of Harris County would carry significant added costs, which builders would pass on to homebuyers.

However, elevating a post frame home, even as much as eight feet, is a negligible investment compared to the costs of stick frame construction. Considering constructing a new home? If so, look towards post frame construction as an affordable design solution.

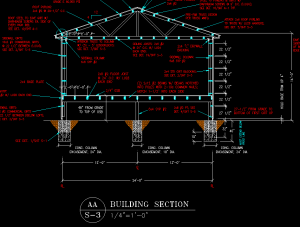

would like to see this blue print bigger by it self ,building section a-a s-3.. thank you

would like more on crawl space

We understood the need prior to clicking on this article. Disappointing that only the very last paragraph uninformatively mentions anything at all relating to the title. Which is what we presumatively came to read about.

Our team would be more than happy to discuss your individual needs Caryn. Please call 1.866.200.9657 for more information.