Pressure Treating Beyond CCA

My friend Sharon Thatcher is the editor of Rural Builder magazine. This article, written by her, was published in the December edition of Rural Builder and is so well done, I felt it was well worth sharing.

It’s been nearly 12 years since new measures were put in place to help resolve a controversy over the use of CCA (chromated copper arsenate) in the treatment of wood products to ward off rot, decay and termites. Although the science of CCA never uncovered any smoking gun to warrant the furor, restricted use is in place and the treatment industry has moved on.

It’s been nearly 12 years since new measures were put in place to help resolve a controversy over the use of CCA (chromated copper arsenate) in the treatment of wood products to ward off rot, decay and termites. Although the science of CCA never uncovered any smoking gun to warrant the furor, restricted use is in place and the treatment industry has moved on.

A quick look back

Kris Owen, retired from Lonza/Arch Wood Protection, and now a private consultant in the industry, was on the front lines when the controversy surfaced.

“There was a movement by the Environmental Protection Agency to take CCA entirely out of the market,” he recalled in a recent interview, noting that this attempt prevailed despite the fact that there had been no serious health problems linked to CCA and even today has over 60 years of documented safe use.

“… the EPA was pushed and prodded both politically and by some environmental groups supposedly sensitive to the issue, who wanted CCA out of the marketplace,” said Owen. “So the roadblocks that the EPA was putting into place would have made it very difficult for the treatment industry to stay only with CCA.”

To head off any further damage, the treatment industry voluntarily restricted CCA for certain applications. It could be used for non-consumer industrial, commercial, marine and agricultural applications such as agricultural timbers and poles, foundation pilings, highway construction, marine, permanent wood foundations, plywood products and utility poles. The primary restrictions were placed on residential applications for lumber.

Alternative treatments begin to emerge

Because of the CCA restrictions, alternative treatments began to gain favor, not just in the U.S., but in countries like Germany and Japan where arsenic-based wood treatment was also under scrutiny.

The current market has stabilized so that micronized products, mainly copper azoles (CuAz), are now the norm.

In a micronized product, the copper is dispersed in water rather than dissolved (like CCA), so that actual copper metal particles, in very small, micronized sizes, are being injected into the wood.

“There were copper azole products and there were copper quaternary products that were available in 2004,” Owen explained. “But it was about 2006 that micronized technology had been field tested to the point where, by 2009, it was pretty much on its way to being a force in the marketplace.”

Meeting today’s standards

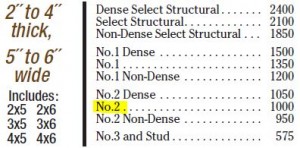

It really isn’t too difficult to meet the building standards for treated wood, but there are some common mistakes and precautions builders should take. First, all wood that meets the standards are labeled with an ICC-ES approval or an AWPA approval and includes information on the chemical used, the standards it meets, the manufacturer’s name and the year of manufacture, as well marked “ground contact” or “above ground” to help the builder identify where it can be used.

The AWPA (American Wood Protection Association) is a non-profit organization that has been setting voluntary treatment standards for the industry since 1904. It is highly regarded for its open, consensus-based process that involves experts from throughout the world and is ANSI accredited.

There is occasionally an attempt by a newcomer to skirt the rules and make or sell sub-par treated products, but Owen is impressed by the wood treatment industry as a whole. “The products being merchandised today by the dealers across America are pretty solid,” he said.

Let the builder beware

A product can be made to all the right specifications but it’s up the builder to make sure it is used properly, and sometimes assumptions can get in the way of facts. One mistake Owen has seen is the use of CCA for splash plank or splash boards commonly found just above post-frame foundations. It makes sense, and in fact the National Frame Building Association (NFBA) did at one time attempt to get CCA approved for that ground-close area of the building.

“In 2003, there was a group [from NFBA] that went to Washington D.C. to meet with the EPA … to get that material to remain in CCA. Because of the difficulty that would cause the dealers in carrying different inventories and the ability for that to be confused with other 2×6, 2×8 material at the lumberyard, the EPA refused the request,” Owen noted. Because of that ruling, the NFBA requirements for the use of treated wood in post frame includes that CCA cannot be used for splash board areas. NFBA also requires that Ground Contact labelled material must be used in splash plank/splash board applications. There remains some confusion by builders over this point of use, however.

Another problem area for builders, Owen noted, is with treated wood that has been cut, drilled or ripped. Field treating is required on those vulnerable areas to assure continued preservation, yet a step that builders often ignore.

“There is an AWPA standard called M4 that is for the field treatment of treated wood,” he said. “There are steps you are supposed to take to re-coat using a variety of chemical products like copper naphthenate on those cut ends,” Owen said.

Knowing that it was often ignored, AWPA has revised the M4 standard to clarify and strengthen field-treatment. “It is relatively new,” Owen said of the standard, “so builders need to know there has been a change.”

Proper fasteners for treated wood

Soon after CCA was restricted, a lot of discussion revolved around what types of fasteners should be used with wood preserved with alternative treatments. CCA was known for its noncorrosive properties, but how would copper azole and copper quandary react to metal?

A barrage of studies commenced. The answer has been relatively simple. As long as you use hot-dipped galvanized or stainless steel fasteners and connectors that meet the ASTM standards, corrosion will not be a problem.

Owen noted that part of the early tests revealed that many fasteners popular at the time were produced overseas and did not meet the new demand. They were only whisper-coated, leaving them vulnerable to corrosion to the alternative wood preservatives.

Only one U.S. manufacturer was prepared for the challenge. “There’s only one USA manufacturer, and that’s Maze Nails, who since 1926 has only met and exceeded the standard in every product they’ve produced,” Owen said.

The fastener industry as a whole, however, stepped up to the challenge. “What this forced them to do is really look at their quality control and the product they were putting out,” Owen said. “So our product (treated wood) certainly did change, but the fastener industry had to change quite rapidly as well to assure that their products were properly coated,” Owen said. “For probably the past 10 years, the industry has done a good job of identifying those products.”

A final word

It is said often enough in the building industry that quality installation assures that you get the most out of the quality of the product itself. This applies to treated wood and to the fasteners used to hold it together. Owen provides this final word: “If a builder buys the right material from his dealer, he’s pretty much assured that that product, used in its proper application, will give the service life expected. The caveat to that is: in its proper use.” RB

That was very interesting Mike thank you for passing that story along.