Code Requirements for Residential Roof Trusses

Reprinted from a March 2019 article in Structure Magazine authored by Brent Maxfield, P.E.

Part 3 of 3:

Implementation

Implementation

1. Building Officials, Contractors, Owners, and Building Designers should be cognizant of and enforce the requirement that the Contractor and the Building Designer review the Truss Submittal Package prior to the installation of the Trusses. Building Officials should establish procedures to ensure that this code requirement is followed.

2. Many engineering drawings have general notes that require the Trusses to be designed and stamped by a registered engineer. It is important to understand that the stamp is for individual Trusses and not for the Trusses acting together as a system. Many engineers falsely assume that this stamp is for the individual Trusses as well as for the roof system.

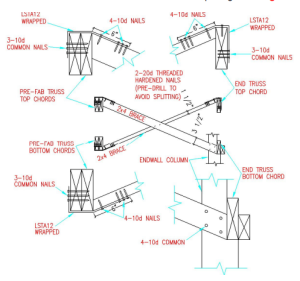

3. Truss web bracing locations are provided on the Truss Design Drawings in the Truss Submittal Package. The BCSI document usually provides the bracing details. Many Truss webs do not align with adjacent Trusses, making continuous Lateral Restraint

bracing impossible to install. In these cases, T or L bracing will be required. Construction Documents should provide details and instructions for when T or L bracing is required.

4. Truss web bracing is critical to the stability of the roof system, yet very few residential projects have engineering observation of completed roof systems. Unless the Truss spans 60 feet or more, special inspection of the Truss web bracing installation is not required. This is an area where the code requirements could be improved.

5. Many projects have general notes that state that snow drift and unbalanced snow loading are required to be considered in the Truss design, but the Construction Documents do not provide the actual values of the snow drift loads and the unbalanced loads for each Truss. This is contrary to ANSI/TPI 1, Section 2.3.2.4(d). It is important to understand that the responsibility for calculating and providing the loads applied to each Truss rests with the Building Designer.

6. A functioning roof system is the responsibility of the Building Designer and consists of Trusses, bracing, blocking, connections to structure, diaphragms, and an understanding of the load path of all forces. The Truss Submittal Package is only one piece of the system.

7. If a portion of the roof system falls outside of the scope of the IRC, then that portion, including the associated load paths, will require engineering analysis. If the Building Designer is not an engineer, then an engineer who is not filling the role of the Building Designer could be engaged for a limited scope to design and stamp the elements that fall outside of the scope of the IRC.

This article intends to educate engineers about the roles and division of responsibilities for residential wood Trusses. It is critical to understand the specific scope of the Truss Designer as defined in ANSI/TPI 1. The Truss Designer is responsible for individual Truss Design Drawings using loading information obtained from the Truss Manufacturer, who gets information from the Contractor in the form of selected information from the Construction Documents. The Building Designer is responsible for ensuring that the Truss loads given to the Truss Designer are accurate. The Building Designer is also responsible for ensuring that all Trusses act together as a roof system. All players need to understand and fulfill their responsibilities as outlined in ANSI/TPI 1 in order to achieve a safe and code-conforming building.

This article intends to educate engineers about the roles and division of responsibilities for residential wood Trusses. It is critical to understand the specific scope of the Truss Designer as defined in ANSI/TPI 1. The Truss Designer is responsible for individual Truss Design Drawings using loading information obtained from the Truss Manufacturer, who gets information from the Contractor in the form of selected information from the Construction Documents. The Building Designer is responsible for ensuring that the Truss loads given to the Truss Designer are accurate. The Building Designer is also responsible for ensuring that all Trusses act together as a roof system. All players need to understand and fulfill their responsibilities as outlined in ANSI/TPI 1 in order to achieve a safe and code-conforming building.

I will mention here, Hansen Pole Buildings takes both temporary and permanent truss bracing quite seriously. Every building we provide includes an engineered permanent truss bracing plan and our Construction Manual has an entire chapter devoted to truss bracing.

I will mention here, Hansen Pole Buildings takes both temporary and permanent truss bracing quite seriously. Every building we provide includes an engineered permanent truss bracing plan and our Construction Manual has an entire chapter devoted to truss bracing.