Pressure Treated Douglas-Fir

Reader ERIC in SANTA CRUZ writes:

“Hello, I am researching pressure treated pole and post treatments. I am looking at UC-4b treatment for long term. I need real life experience with Douglas fir using CCA-C . The other consideration is Douglas Fir using ACZA.”

“Hello, I am researching pressure treated pole and post treatments. I am looking at UC-4b treatment for long term. I need real life experience with Douglas fir using CCA-C . The other consideration is Douglas Fir using ACZA.”

Mike the Pole Barn Guru says:

Early in my post frame building career, I worked for Lucas Plywood and Lumber in Salem, Oregon. Owner Virgil Lucas would (about once a month) have our lumber yard crew gather up all dimensional lumber beginning to have a ‘sun tan’ (turned grey from being outdoors in weather) and send it off to be CCA pressure treated. His thought was this would hide discolorations. Well, hiding off color was correct, however much of this lumber was Douglas-fir and ended up basically being painted green from chemical preservatives, but actually not being anything close to adequately treated.

Today most CCA is composed of a mixture of oxides of chromium, copper and arsenic. Each component has a specific function — copper as a fungicide, arsenic as an insecticide, and chromium as a bonding agent, which “fixes” everything to wood. CCA treating mixture is supplied as a liquid concentrate, is diluted with water to appropriate level and then injected into wood under high pressure in large steel treating cylinders. After wood has absorbed all of the treating solution it can absorb, pressure is removed and a short vacuum is applied to pull off excess liquid. This wood is then air- or kiln dried before being shipped to lumber yards.

Once inside wood’s cellular structure, CCA treating solution undergoes a complex series of chemical reactions with major wood components — cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin. These reactions result in a bonding of CCA ingredients to wood fibers, rendering these chemicals insoluble and resistant to water-leaching.

In order to accept CCA preservative solution, green lumber is usually dried to a moisture content of 25% or less. This is accomplished by either kiln drying or air seasoning. During treatment, wood fiber becomes completely saturated with preservative solution, being mostly water. After the treatment process is complete wood is still virtually 100% water saturated.

Highest grades of treated wood are kiln dried after treatment to bring moisture content down to 19% or less. However, it is more typical to allow this wood to air dry to reach equilibrium moisture content. In some cases treated wood will reach lumber yards while still very wet.

Many types of softwood can be pressure treated with CCA preservative; however, the most commonly treated species is Southern Yellow Pine. In the West, Hemlock, Hem-fir, Ponderosa Pine, Jack Pine and Red Pine are also subject to CCA treatment. Some species, such as Douglas fir, have difficulty accepting waterborne treatments; these are said to be refractory. To promote penetration of preservatives, these woods are sometimes mechanically incised before treatment. Treated lumber will then have characteristic rows of incising marks. (Read more about incising here: https://www.hansenpolebuildings.com/2014/08/incising/).

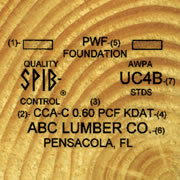

American Wood Protection Association (AWPA) set standards for United States pressure-treated wood. These standards set requirements for preservative level in wood, depth of penetration, treatable species and other important treating parameters. Adherence to standard is checked by way of third-party inspection at treating plants. Those treaters who consistently meet AWPA standards are allowed to display AWPA and third party inspection agency marks on their lumber.

Treated lumber will also often bear a grade stamp and a mark designating level of CCA treatment. Grade stamps are similar to those for untreated lumber. CCA level is listed as a retention number, which represents pounds per cubic foot (pcf) of preservative in wood. For above-ground applications specified retention of CCA is 0.25 pcf, for ground contact uses it is 0.40 pcf, and for structural in ground use it is 0.60 pcf.

Fixation and leaching characteristics of chromated copper arsenate (CCA)-treated Douglas-fir sapwood and heartwood have been evaluated using expressate method and American Wood Protection Association (AWPA) El 1-97 leaching procedure. CCA fixation, monitored by hexavalent chromium reduction, was much faster in heartwood than in sapwood; copper and arsenic fixation in heartwood appeared to be incomplete, regardless of duration of fixation time. Poor fixation of copper and arsenic in heartwood was confirmed using leaching tests. Based on results, it has been concluded CCA is not an appropriate preservative for Douglas-fir heartwood because of its poor fixation quality.

Due to this, ACZA remains the first choice for pressure treating Douglas-fir. You may want to consider the use of Hem-fir treated to UC-4B standards with CCA, MCQ or MCA due to pricing and availability issues.

Pressure-treated wood is treated to various retention levels which are intended to protect the wood for particular applications. Retention levels indicate the amount of preservative retained in the wood in a specific assay zone. In North America, retention is expressed in pounds per cubic foot (pcf).

Pressure-treated wood is treated to various retention levels which are intended to protect the wood for particular applications. Retention levels indicate the amount of preservative retained in the wood in a specific assay zone. In North America, retention is expressed in pounds per cubic foot (pcf). Difficult-to-treat (refractory) lumber species, such as Hem-Fir, must be incised prior to preservative treatment to meet minimum penetration requirements for preservative-treated wood. Incising is a pretreatment process in which small incisions or slits are punched into the wood. To me, the resultant product looks as though the lumber has been walked on by someone wearing golf shoes!

Difficult-to-treat (refractory) lumber species, such as Hem-Fir, must be incised prior to preservative treatment to meet minimum penetration requirements for preservative-treated wood. Incising is a pretreatment process in which small incisions or slits are punched into the wood. To me, the resultant product looks as though the lumber has been walked on by someone wearing golf shoes!