Thinking Stick Frame Rather Than Post Frame

Reader BRAD writes:“Real question…I’ve been doing lots of reading and love this site. I am building a 40x60x14 this spring. I originally thought I was going to go pole barn and now I am thinking stick frame. Reason….1. I am going to have insulated concrete foundation with in floor heating piping installed right away. (mono slab). 2. I am planning on fully finishing the inside insulation electrical, etc. in the future. What I’ve seen with post frame is that they are cheaper to build initially but if you are planning on finishing the inside there is substantial lumber and framing that needs to be done for interior walls and interior ceiling. It appears “at the end of the day” a finished pole barn is not much cheaper than a stick frame. I also question if it would be a lot more time trying to frame an interior post frame with 16” o/c studs and finishing a ceiling with 4’ or longer truss spacing vs 2’ with conventional stick frame. I am doing all metal exterior with 2’ o/c stud purlins on side walls vs osb sheathing. I know you can spray closed cell spray foam but again that is more than triple the price vs bats and vapor barrier that you can only do with 24”or16” o/c framing.

Am I way off base on this theory or is there any truth to my thinking?”

Mike the Pole Barn Guru responds:

Mike the Pole Barn Guru responds:

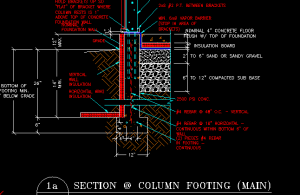

I just don’t see reason number one as a reason at all. A plethora of post frame buildings (my own included) utilize radiant in-floor heat. In order to stick frame, you are going to have to thicken your slab edges, or pour a continuous footing and stem wall, in order to provide adequate support for your now load bearing walls. This is going to result in added expenses for forming, regardless of your choice (before even considering extra concrete required). While anchor bolts for stud walls are relatively inexpensive, they do require some effort to be properly placed in order to avoid hitting studs and plates need to be drilled to account for them.

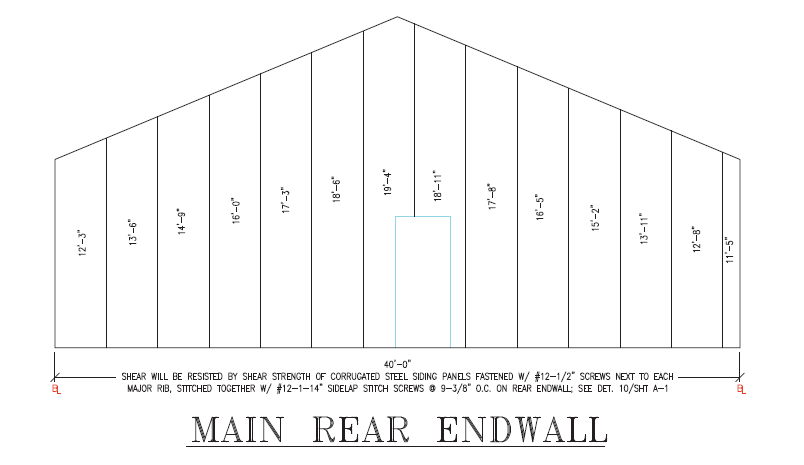

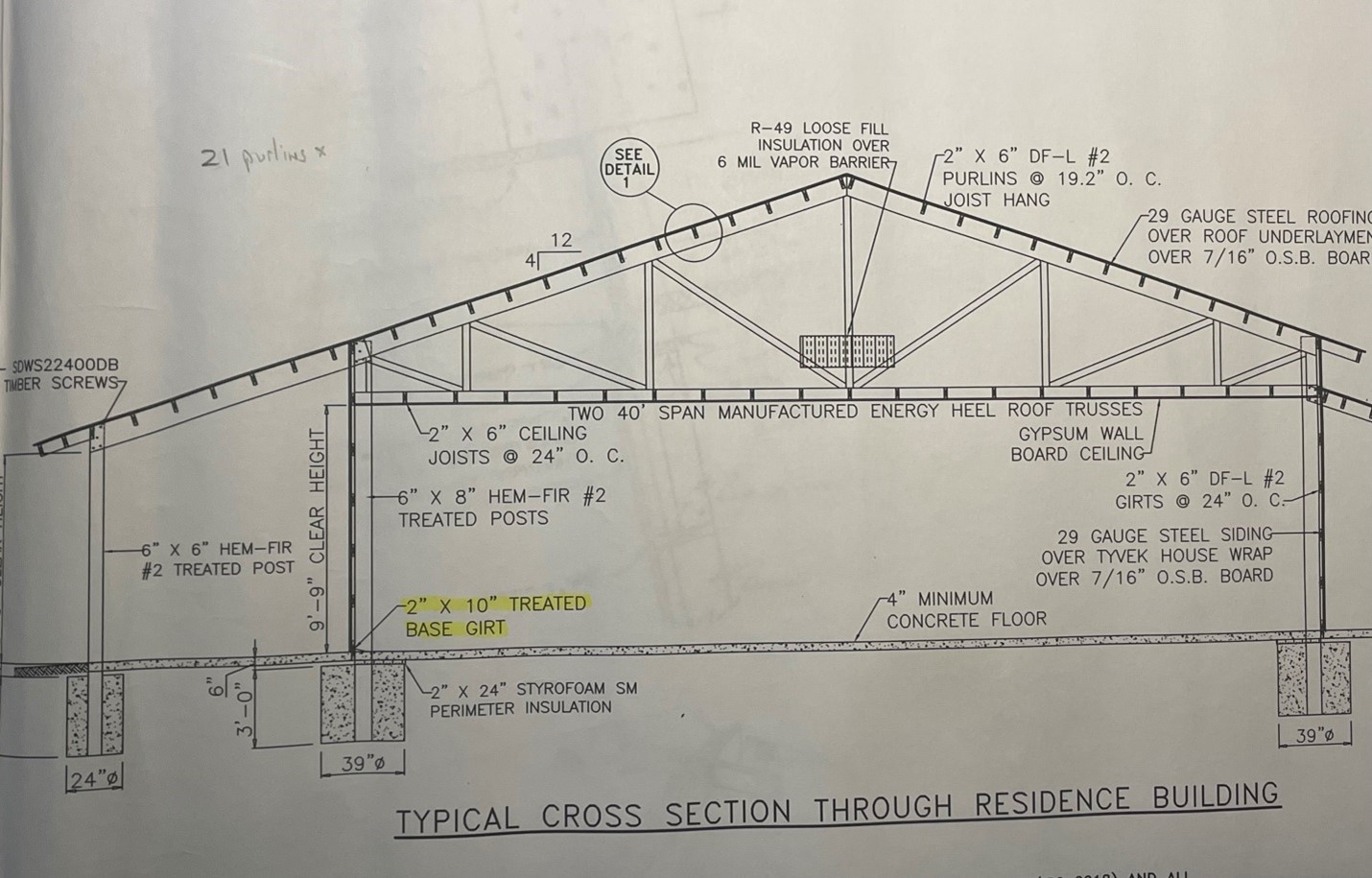

In order to stick frame without added engineering, your wall heights are going to be limited by Building Codes. To attach steel siding, you will need to add horizontal framing outside of your studs (scarily, I did see a builder post photos of vertical steel siding, screwed to vertical studs), resulting in two sets of framing, extra pieces to handle, cut and install. By using commercial style bookshelf wall girts in post frame, no extra framing is required in order to attach exterior steel siding and wall finish of your choice. As post frame buildings transfer gravity loads from roof-to-ground via columns, eliminating (in most instances) any need for structural headers.

Using prefabricated metal connector plated wood trusses, in pairs, directly aligned with columns (most often placed every 12 feet), does require ceiling joists to be placed between truss pairs. This can all be done on the ground, then cranked into place using winch boxes, with no need for other heavy lifting equipment.

When all is said and done, fully engineered post frame construction will always be more cost effective than stick frame, more structurally sound and afford a greater ability to super insulate, regardless of one’s choice of insulation systems.

When you create an encapsulated building (spray foam to all interior surfaces), you do not want to ventilate it, as you would then lose your air seal. With your OSB’s underside sealed by closed cell spray foam and upper side protected with 30# felt or ice and water shield, there is no way for your OSB to become moist. If this is still a concern, an upgrade to plywood could be done.

When you create an encapsulated building (spray foam to all interior surfaces), you do not want to ventilate it, as you would then lose your air seal. With your OSB’s underside sealed by closed cell spray foam and upper side protected with 30# felt or ice and water shield, there is no way for your OSB to become moist. If this is still a concern, an upgrade to plywood could be done. We do have sample building plans available on our website for your builder to review and get a feel for

We do have sample building plans available on our website for your builder to review and get a feel for  My first recommendation would be to construct the ultimate sized shell and only finish off interior of what you immediately need and will fit within your budget. Done in pieces doubles the number of deliveries made to your site and trucks do not run for free.

My first recommendation would be to construct the ultimate sized shell and only finish off interior of what you immediately need and will fit within your budget. Done in pieces doubles the number of deliveries made to your site and trucks do not run for free.  We look for trends in questions asked by owners of existing pole barns – usually not even those we provided! There are a couple of these our team has decided to address and we have so far done a very poor job of letting our clients know we have done so.

We look for trends in questions asked by owners of existing pole barns – usually not even those we provided! There are a couple of these our team has decided to address and we have so far done a very poor job of letting our clients know we have done so. Going to a longer part solved the pull out issues in our testing. We also went to a larger diameter part in our testing, the shank below the screw heading being ¼ inch across, while the threads are a #12. The larger diameter screws also have deeper threads, which means they bite and grip the wood more tightly.

Going to a longer part solved the pull out issues in our testing. We also went to a larger diameter part in our testing, the shank below the screw heading being ¼ inch across, while the threads are a #12. The larger diameter screws also have deeper threads, which means they bite and grip the wood more tightly.